Music’s Impact on the Brain

Diyaa Rahmani, Master’s student in psychology at the University of Montreal

Isabelle Peretz, Professor in the psychology department of the University of Montreal

For millennia, music has been used as a form of artistic expression. Music, as a universally appreciated art, holds an extraordinary power over our brain, influencing our emotions, thoughts, and even behaviors. This extends far beyond aesthetic considerations: music has the capacity to shape our brain in profound and intricate ways. In this article, we will delve into recent findings and fascinating insights that have illuminated how music modifies our most complex organ.

Music Shapes the Brain

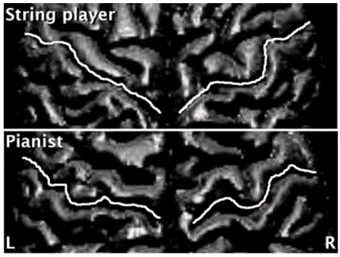

Researchers have delved into investigating whether there are anatomical brain differences between musicians and non-musicians. A study conducted by Bangert and Schlaug (2006) demonstrated that the brains of violinists and pianists differ from those of non-musicians in terms of the motor cortex responsible for hand movements. They found that in violinists, this region in the right hemisphere (which controls the left hand) takes on a reverse omega (Ω) shape. In pianists, the omega shape is present in both hemispheres, as they utilize both hands for playing.

Figure 1: 3D MRI Illustration of the Brain of a Violinist and a Pianist (Bangert & Schlaug, 2006)

More than just a visual change

Learning a musical instrument goes beyond mere visual brain shaping. It also triggers the generation of new neurons in regions dedicated to musical perception, such as the temporal lobe and the superior temporal gyrus (Bermudez et al., 2009). Moreover, research by Kraus and Chandrasekaran (2010) has demonstrated that regular musical practice stimulates neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to restructure and adapt in response to new experiences. By playing an instrument, musicians develop more intricate and sophisticated neural circuits in areas associated with auditory processing and musical comprehension. This translates into improved musical skills, as well as a heightened perception and interpretation of sounds.

Benefits that go beyond music

Furthermore, musical learning also activates the motor regions of the brain, as playing an instrument involves precise coordination of movements. This stimulation of motor areas results in enhanced hand-eye coordination and dexterity, both essential for producing accurate sounds. Lastly, musical practice strengthens connections between auditory and motor areas, as well as the frontal cortex responsible for higher cognitive functions like planning, organization, and decision-making. This heightened synergy across various brain regions can prove beneficial even for non-musical tasks, enhancing learning abilities and problem-solving skills.

Urban circuits and neural circuits: The example of London

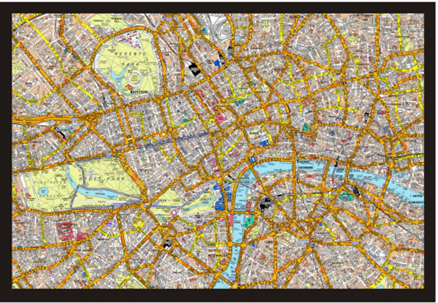

This brain plasticity isn’t exclusive to music learning; it’s often observed following sustained and deliberate learning. For instance, consider London taxi drivers. The city of London, with its intricate network of 25,000 streets within a 10-kilometer radius (Figure 2), forms a true labyrinth. To obtain a taxi driver’s license, apprentice drivers must navigate this network without the aid of GPS. It takes approximately 3 to 4 years of training to confidently navigate the city.

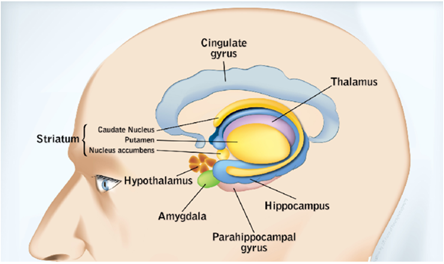

Researchers were curious to investigate whether the brain of these apprentice drivers would undergo changes because of this learning process (Woollett & Maguire, 2011). Through magnetic resonance imaging, they scanned the participants’ brains before and after their training. They then analyzed various brain regions, including the hippocampus – a region within the limbic system that’s vital for spatial navigation and long-term memory (Figure 3). The researchers discovered that taxi drivers who successfully passed the test had a larger hippocampus than they did four years prior and had a larger hippocampus in contrast to those who failed the test.

This intriguing finding suggests that intensive, complex learning experiences can reshape the brain’s structure, even in regions associated with memory and spatial navigation. Just as musical training enhances certain cognitive abilities, navigating London’s intricate streets influences the hippocampus, reinforcing the concept of neuroplasticity and the brain’s remarkable capacity to adapt to new challenges.

Figure 2: Map of London. (Woollett & Maguire, 2011)

Figure 3: Image of the Limbic System, the Brain’s Oldest Region

Can music make us smarter? A myth or reality?

The question of whether listening to music can make us smarter has garnered considerable interest since the famous 1993 experiment. This study, conducted with 36 adolescents, demonstrated that listening to Mozart’s music for 10 minutes temporarily improves performance on a test measuring spatial intelligence (Rauscher et al., 1993). Despite the specific conditions mentioned in the study, there has been misinformation about the research in the media, suggesting that listening to Mozart’s music can make us more intelligent. This is why, even today, you can find books on the benefits of Mozart’s music on infants’ brains or CDs containing several of his compositions to play for infants in order to stimulate their intellect.

Several other studies have replicated Rauscher and her colleagues’ research and found similar results. For example, the study by Nantais and Schellenberg (1999) aimed to confirm this theory. Their results indicated that participants who listened to Mozart’s music for 10 minutes scored better on a mental rotation test than those in a silent environment. However, they also found that there was no significant difference in scores between participants who listened to Mozart’s music and those who listened to a narrated story. These results suggest that it’s not specifically Mozart’s music that enhances performance but rather listening to what one enjoys that promotes concentration and attention during a task (Peretz, 2018).

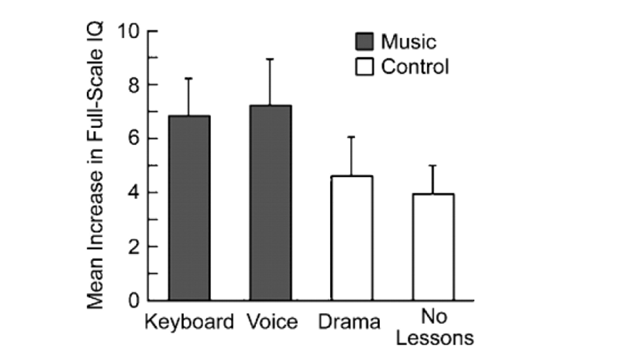

So, if listening to music doesn’t enhance our cognitive abilities, can playing an instrument improve them? Studies demonstrate that individuals who engage in musical practice from a young age develop certain cognitive skills more advantageously than those without musical training. Schellenberg (2004) tested 144 children who were randomly assigned to four groups. The children either took piano lessons, singing lessons, drama lessons, or no lessons. He measured the children’s intellectual abilities before and after the lessons using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. He found that children who took music lessons (either piano or singing) had a higher increase in their overall IQ scores compared to those who took drama lessons or no lessons (Figure 4). This suggests that music significantly impacts the developing brains of children, stimulating various brain regions including auditory perception, memory, and motor coordination.

Figure 4: Graph illustrating the average increase in overall IQ score after completing the lessons.

However, it’s crucial to note that the relationship between music and intelligence is complex, and it isn’t a straightforward connection. Musical practice can certainly contribute to improved cognitive abilities, but it doesn’t necessarily mean musicians are inherently more intelligent than non-musicians.

The Effects of Learning Music Later in Life

Individuals who have engaged in musical practice from a young age seem to have a shield against age-related cognitive decline. While musicians also experience hearing loss with age, their brains retain an enhanced ability to discern incoming sounds. Alain and colleagues’ study (2014) demonstrated that at the age of 70, a musician can comprehend speech in noise similarly to a non-musician who is merely 50. Early musical learning also aids in perceiving speech in noisy environments during advanced age. Exposure to music from an early age sharpens auditory acuity, enabling better focus on conversations despite background noise. This aptitude to differentiate sounds in noisy settings proves invaluable for the elderly who might otherwise struggle to follow conversations in noisy surroundings. Thus, musical learning plays an essential role in maintaining auditory and cognitive quality as we age.

Remarkably, one doesn’t need a lifelong musical practice to reap these positive effects. Even after discontinuing musical engagement, the benefits persist. A study reveals that advantages endure in individuals who underwent musical training for about 4 to 14 years before the age of 25, even if they ceased practice for 40 years thereafter (White-Schwoch et al., 2013). This finding is encouraging, suggesting that relatively short and early musical learning experiences can have enduring brain benefits. Neurological changes and skills acquired through musical practice appear to last over time, contributing to improved auditory perception and an enhanced ability to discern sounds, even after an extended period of inactive musical practice.

It’s never too late to embark on musical learning and reap its rewards. A study conducted among 70-year-olds demonstrates that even at this age, initiation into music can yield significant positive effects (Seinfeld et al., 2013). After just four months of piano learning and musical literacy courses, these elderly individuals exhibited notably improved mood and enhanced executive functions, especially attention and planning. Elderly participants engaged in other activities like physical exercise, computer use, or painting didn’t experience the same gains (Seinfeld et al., 2013).

Music is far more than mere entertainment. It holds a captivating power over the human brain, shaping and significantly influencing its functions. It’s important to note that the effects of music on the brain can vary among individuals and are also influenced by the quantity and regularity of musical exposure.

Also, worth knowing

Another benefit of engaging in music is that it serves as an excellent means of socialization. Making music in a group setting enhances social bonds and is often associated with intense and pleasant emotions. Several studies, including those by Pearce and colleagues (2017) and Kreutz (2014) have demonstrated that group singing promotes the development of social connections and a sense of well-being. For further insights, here are some article links to explore.

Does singing facilitate social bonding? (apa.org)

Credit

All the topics covered in this article are discussed in the book “Apprendre la musique, les nouvelles des Neurosciences” by Isabelle Peretz, a full professor at the University of Montreal.

Bibliography

Alain, C., Zendel, B. R., Hutka, S., & Bidelman, G. M. (2014). Turning down the noise : The benefit of musical training on the aging auditory brain. Hearing Research, 308, 162‑173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2013.06.008

Bangert, M., & Schlaug, G. (2006). Specialization of the specialized in features of external human brain morphology. European Journal of Neuroscience, 24(6), 1832‑1834. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05031

Bermudez, P., Lerch, J. P., Evans, A. C., & Zatorre, R. J. (2009). Neuroanatomical correlates of musicianship as revealed by cortical thickness and voxel-based morphometry. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991), 19(7), 1583‑1596. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn196

Kraus, N., & Chandrasekaran, B. (2010). Music training for the development of auditory skills. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(8), 599‑605. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2882

Kreutz, G. (2014). Does singing facilitate social bonding? Music and Medicine, 6(2), 51‑60.

Nantais, K. M., & Schellenberg, E. G. (1999). The Mozart Effect : An Artifact of Preference. Psychological Science, 10(4), 370‑373. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00170

Pearce, E., Launay, J., MacCarron, P., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2017). Tuning in to others : Exploring relational and collective bonding in singing and non-singing groups over time. Psychology of Music, 45(4), 496‑512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735616667543

Peretz, I. (2018). Apprendre la musique : Nouvelles des neurosciences. Odile Jacob.

Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L., & Ky, K. N. (1993). Music and spatial task performance. Nature, 365(6447), 611. https://doi.org/10.1038/365611a0

Schellenberg, E. G. (2004). Music Lessons Enhance IQ. Psychological Science, 15(8), 511‑514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00711

Seinfeld, S., Figueroa, H., Ortiz-Gil, J., & Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2013). Effects of music learning and piano practice on cognitive function, mood and quality of life in older adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00810

White-Schwoch, T., Carr, K. W., Anderson, S., Strait, D. L., & Kraus, N. (2013). Older Adults Benefit from Music Training Early in Life : Biological Evidence for Long-Term Training-Driven Plasticity. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33(45), 17667‑17674. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2560-13.2013

Woollett, K., & Maguire, E. A. (2011). Acquiring “the Knowledge” of London’s Layout Drives Structural Brain Changes. Current Biology, 21(24), 2109‑2114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.018